Right, let’s talk about something that, on the surface, sounds about as exciting as watching paint dry. Standardised work. I know, I know. The phrase itself probably conjures up images of old black and white factory footage, rows of identical workers doing identical tasks with robotic precision. It feels rigid, a bit soul crushing, and completely at odds with the dynamic, creative, and, let’s be honest, slightly chaotic way most of our businesses actually run.

And that’s the problem right there. It’s one of the most powerful, transformative tools in the entire lean manufacturing playbook, yet it remains one of the least understood and least used. Why? Because we’ve completely misunderstood what it’s for.

From my own experience working with countless teams, I can tell you this with absolute certainty: without standards, you do not have continuous improvement. What you have is chaos. You have firefighting. You have good days and bad days that you can’t quite explain. You have a constant, draining variability that makes progress feel like guesswork.

I’ve heard all the rebuttals, and I’m sure you have too. They usually come from very smart, passionate people who genuinely believe their work is different.

“We don’t make cars, you know.”

“You see, our process is creative. It can’t be standardised.”

“We’re unique… this isn’t an assembly line!”

And I get it, I really do. The objection comes from a good place, a desire to protect the craft, the human element, the spark of ingenuity that makes their work special. But here’s the thing I always say in response. Everyone, and I mean everyone, works a process. That process, whether you’re designing a marketing campaign, admitting a patient to a hospital, writing code, or yes, building a car, can only be doing one of two things. It’s either creating value for your customer, or it’s destroying it. Which would you rather it be?

It doesn’t matter if you’re delivering lifesaving patient care or assembling a gearbox. The end result relies on a sequence of highly coordinated tasks and processes. When you find a way to standardise the best-known method for that sequence, you’re not killing creativity. You’re clearing the path for it. You are beginning the journey of fundamentally improving your work and eliminating the significant, often hidden, sources of waste that frustrate your team and disappoint your customers.

The Great Misunderstanding: “But Our Work is Special”

Let’s dig into that pushback a little more, because it’s the single biggest barrier to getting started. The idea that standardisation is only for the factory floor is a myth, but it’s a persistent one.

Imagine the head of a busy A&E department. Their environment is the definition of unpredictable. Every case is different, every patient unique. The idea of a “standard” way of working seems almost insulting to the skill and judgement of the doctors and nurses. But think about the process of triage. Is there a standard set of questions to ask to assess urgency? Is there a standard procedure for checking vital signs? A standard location for the crash cart? Of course there is. These standards don’t restrict a doctor’s ability to make a complex diagnosis. They do the opposite. They handle the repeatable, critical basics flawlessly every single time, freeing up the doctor’s mental energy to focus on the difficult, unique aspects of the patient’s condition. Without those standards, you get chaos, missed steps, and potentially tragic errors.

Or what about a team of software developers? They’re the epitome of modern knowledge work. Their job is to solve complex problems with elegant code. You can’t standardise creativity, right? Well, no, you can’t standardise the moment of inspiration. But you can absolutely standardise the process around it. How does the team handle bug reports? Is there a standard way to test new code before it’s deployed? A standard checklist for releasing an update to prevent servers from crashing at 2 a.m.? These standards don’t tell a developer how to write a brilliant algorithm. They create a stable, predictable framework so that their brilliant algorithm can be delivered to users reliably and without causing new problems. They prevent the team from constantly reinventing the wheel on routine tasks.

The truth is, every job has elements that are repeatable. Standardised work isn’t about the whole job; it’s about those repeatable parts. It’s about agreeing, as a team, on the best way we currently know how to do a specific task. By doing this, we create a baseline. A stable foundation. And you cannot improve something that isn’t stable. Trying to improve a chaotic process is like trying to measure a moving object with a ruler made of elastic. The data you get is meaningless.

So, the next time you hear “we’re different,” the answer isn’t to argue. It’s to ask a different question. “What parts of our work are repeatable? And for those parts, have we agreed on the best way to do them?” The conversation that follows is often the first real step toward meaningful improvement.

So, What Is It, Really?

At its heart, standardised work is incredibly simple. It’s the documented, current, best practice for completing a task. It’s a living document that captures the most efficient and effective way we know right now to get a job done to the highest quality. The goal is to ensure that the same results are achieved, in roughly the same amount of time, with the same level of safety and quality, regardless of who on the team completes the task.

The key word in that definition is current. This is not about carving a process into stone tablets to be handed down from on high. It’s not a rigid, top-down procedure manual that gets written once and then gathers dust in a forgotten folder on the company server. To be honest, that kind of documentation is worse than useless; it breeds cynicism.

Standardised work is the opposite of that. It’s a tool for the people actually doing the work. It’s a dynamic agreement, a hypothesis that says, “Based on everything we know today, this is the best way to do this.” And tomorrow, we might find a better way. When we do, we test it, prove it, and then we update the standard. It’s the engine of kaizen, or continuous improvement.

Think of it like a professional chef’s recipe. A Michelin starred chef has a precise, documented recipe for their signature dish. Every ingredient is measured, every step timed, every technique specified. This doesn’t stifle their creativity. It ensures that every customer who orders that dish gets the same brilliant experience. The standard recipe is the foundation. It’s what allows the kitchen brigade to perform flawlessly under pressure. The creativity happened when the chef was developing the recipe, experimenting with ingredients and techniques. And if they discover a better way to sear the scallops or a new spice for the sauce, they don’t just do it randomly. They test it, perfect it, and then they update the master recipe. They change the standard.

That is what we’re aiming for. A clear, agreed upon method that removes ambiguity and inconsistency from our routine tasks, freeing up our minds to focus on the real problems and the next improvement.

The Building Blocks of a Good Standard H2

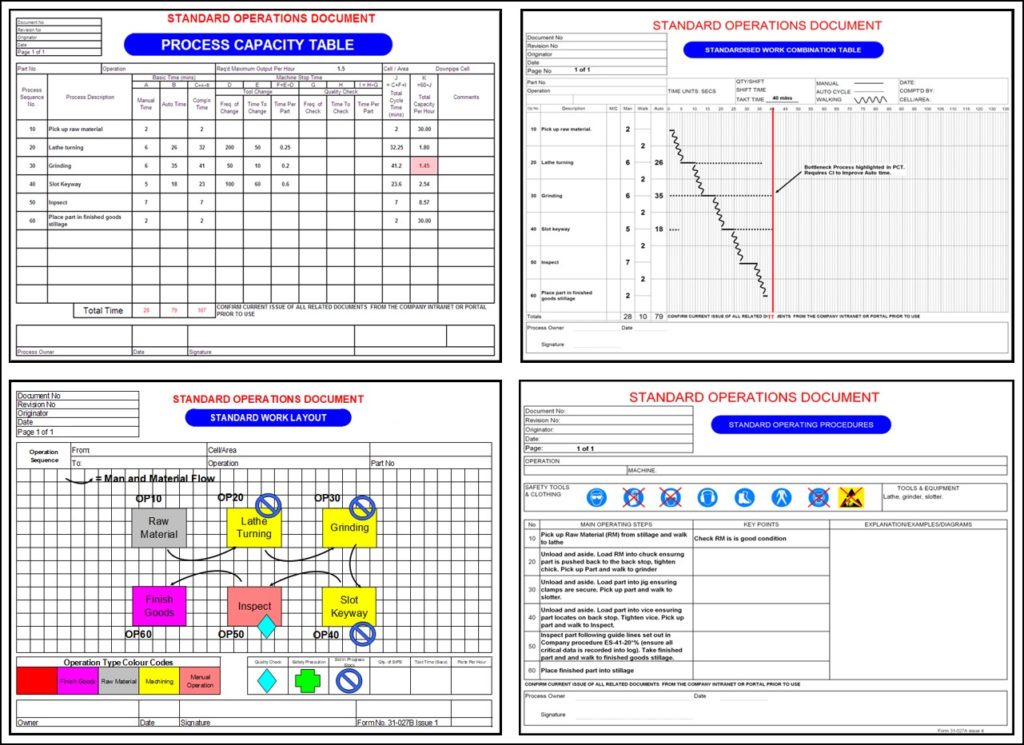

While the specific document might look different in an office versus on a factory floor, the core principles and key elements remain remarkably consistent. To build effective standardised work, you generally need to understand three key components.

1. Takt Time

This is a concept that often gets confused with cycle time, but they are very different things. “Takt” is a German word, and it means beat, or rhythm, like the baton of a conductor keeping an orchestra in time. In a business context, Takt time is the rhythm of your customer demand. It’s the rate at which you need to complete a product or a service to keep up with what your customers are asking for.

The calculation is simple:

Takt Time = Your Available Production Time per Day / Your Customer Demand per Day

Let’s use a non-manufacturing example. Imagine a mortgage processing team that has 420 minutes of available work time in a day (after breaks and meetings). The company receives, on average, 70 mortgage applications per day that need to be processed.

Takt Time = 420 minutes / 70 applications = 6 minutes per application.

This number is profound. It’s the heartbeat of the operation. It tells the team that to meet customer demand, one completed application needs to roll off their production line, so to speak, every six minutes. It’s not about how long it actually takes to do the work (that’s cycle time). It’s about the pace required to satisfy the market. Understanding Takt time helps you design your processes. If the team’s current process takes 10 minutes, you immediately know you have a problem. You can see the gap between your capability and your customer’s expectation, and that’s where your improvement efforts should focus. It prevents overproduction (working faster than needed, which builds up inventory and waste) and underproduction (working too slow, which leads to backlogs and unhappy customers).

2. Work Sequence

This is the most straightforward part. As the great Taiichi Ohno of Toyota put it, it is “The time for an employee to do a prescribed task and return to his original stance.” It is the actual step by step sequence of actions that a person performs to complete one cycle of their work within the Takt time.

A good work sequence is clear, logical, and focuses on the most efficient path of action. It’s not a dense paragraph of text. It’s usually a numbered list, often accompanied by pictures or diagrams, that breaks the task down into its core elements. What is the first thing you do? What is the second? Where do you get your materials from? What tool do you use? It captures the how of the job in a way that is easy for anyone to follow. This ensures that everyone is following the same best practice, which is the key to reducing variation and defects.

3. Standard Inventory

This third element is often overlooked, especially in service or office environments. In manufacturing, it’s easy to understand. It refers to the minimum number of parts or materials needed at a workstation to complete the work smoothly without interruption. You need enough to keep working, but not so much that you’re creating clutter and excess inventory.

In other sectors, the “inventory” might be different, but the principle is the same. For a software developer, it could be the number of open tasks in their “to do” column. Too few and they risk being idle; too many and they suffer from context switching and an overwhelming workload. For a call centre agent, it might be the number of reference documents they need open on their screen to answer customer queries effectively. For a doctor, it could be the standard number of patient files to have ready for their next appointments.

Standard inventory is about defining the minimum resources necessary to perform the job according to the standard work sequence and within the Takt time. It’s about ensuring the process flows without hiccups or delays caused by searching for information, tools, or materials.

Putting It All Into Practice: A Few Ground Rules

Knowing the theory is one thing, but actually creating and sustaining a culture of standardised work is another. It requires a thoughtful, human centred approach. Here are a few things to bear in mind.

First, and most importantly, involve the employees. The people who do the work every day are the experts. A manager sitting in an office trying to write a standard for a task they haven’t performed in years is a recipe for disaster. The standard will be wrong, and the team will resent it and ignore it. The best standards are created when a leader facilitates a conversation with the team, at the place where the work is done. You observe the process together, you time the different steps, and you collectively agree on what the current best practice is. This builds ownership and engagement. When the team creates the standard, they are far more likely to adhere to it and, even better, to improve it.

Focus on the gritty details. A standard that is too high level is useless. Its purpose is to reduce variation, and variation lives in the details. You need to capture the little nuances, the “tricks of the trade.” I remember working with one process where an associate had to physically lean on one part to get another part to fit correctly. A slight tolerance stack up in the components meant it was the only way. This “knack” had to be written into the standard work. Now, was that the long-term solution? Of course not. But documenting it made the problem visible to everyone, including the engineers. It quantified the issue. Imagine the lost time and production if a new person started, wasn’t told about the trick, and spent hours struggling. By documenting the knack, we created a temporary standard while a permanent engineering solution was developed to fix the root cause. Without that detail, the problem remains hidden in tribal knowledge.

Use visuals whenever you can. Our brains are wired to process images far more quickly and effectively than text. A single photograph with a few key annotations can convey more than a full page of written instructions. Use diagrams, photos, examples, and even colour coding to bring your standard work to life. A picture really is worth a thousand words, and it helps overcome language barriers and differences in reading comprehension. The goal is instant clarity.

Make it accessible. This seems obvious, but it’s a common failure point. The documentation is no good if it’s locked in a filing cabinet or buried in a complex server directory. The standard work needs to be available at the point and time that the work is actually being performed. Laminated sheets at the workstation, a monitor displaying the steps, a tablet with the instructions readily available. If a team member has to walk away from their work area to find out how to do their job, the system has failed.

Finally, build a system to innovate. This is the crucial point that prevents standardisation from becoming stagnation. While you don’t want employees deviating from the standard work on a whim, you absolutely must have a clear and simple process for them to suggest improvements. When someone has a new idea, a better way, there needs to be a method to consider it. This is often handled through a governance process or a kaizen suggestion system. It allows the new idea to be tested, analysed, and, if it proves to be better, for it to be approved and rolled out as the new standard for everyone. This creates a positive feedback loop. It tells the team, “We value your expertise, and we want your ideas.” The standard isn’t a cage; it’s simply the starting line for the next improvement.

Standardised work isn’t the most glamorous tool. It doesn’t have the futuristic appeal of AI or automation. But it is, without a doubt, the bedrock of operational excellence. It’s about creating stability in a chaotic world. It’s about respecting the people who do the work by capturing their collective knowledge. And most of all, it’s about building a solid foundation, a floor from which your entire team can rise, together, to new levels of performance. It’s time we stopped dismissing it and started seeing it for what it truly is: the starting point of all meaningful improvement.

Ready to Go Beyond the Basics?

Body: Standard Work is a cornerstone of Lean, but it’s just one tool in the toolbox. Our Lean Green Belt training gives you the complete framework to lead impactful improvement projects from start to finish.

Learn More About Green Belt Certification